Africana Berlin, a Short Tour

Africana Berlin, a Short Tour

Part 1 of articles about Berlin’s African Diaspora(s)

Contacts between the people we call nowadays “Germans” and people from Africa are known at least from the Middle Ages. Some came sporadically to study in monasteries, some arrived in other ways. Much of the African community in Germany has its roots in exploitation, colonialism and the slave trade. Take for example Anton Wilhelm Amo, who was snatched by Dutch merchants in 1707 from his family in the Axim region of nowadays Ghana and “given as a present” to Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel. He received education from the Duke and later studied at the University of Halle (as many 18th Century scholars, he studied a variety of subjects, including law, philosophy, anatomy, theology and more. In 1736, he was made a professor of philosophy at the University of Halle and later in Jena. Unfortunately, by the 1740s he was encountered by anti-liberal and racist treatment that left him returning to his native Ghana. According to some reports, he was promptly arrested there by the Dutch, who feared the eloquent intellectual. Amo did not travel to Berlin, but he is significant enough, as the first African to have studied in a German university, to be mentioned in our trip to Berlin’s Afro-German past.

Colonialism

Germany itself has a shameful colonial history in Africa and in the Pacific Islands. It was shorter (and less geographically extensive) than its French, English or even Dutch counterparts, which in turn impacted the fact, that only few people in former German colonies speak German today. Having said that, the German colonial mindset was similar to that of its counterpart and generated unfortunately racism and violence. There are many memorials you can see in a Berlin tour regarding the culture of memory but there is no official memorial to commemorate the victims of the Genocide of the Herero and the Nama in Namibia. There is a small memorial in the Columbiadamm cemetery

… And Anti-Colonialism

Some Africans who lived in Berlin continued to be active from Germany, in order to fight colonialism and later also racism. Some of them found themselves stateless after the German colonies have fallen by the end of the First World War – they couldn’t return “home” since the new colonial masters were not welcoming, but they were trapped in Germany, which was increasingly raising the ugly head of racism.

Born in Cameroon, Martin Dibobe became a train conductor – later an engineer – for the Berlin budding underground trains, right with the opening in 1902. In 1919, he published – together with several other African-Berliners – the Dibobe-Petition, calling for equal rights for residents from and in the colonies. Dibobe died in Liberia, after being denied entrance to his native Cameroon by the French rulers.

Today, you can find a small memorial for Dibobe in the Hallesches Tor train station, that was part of his line, and a larger memorial plauqe, with more information, in the entrance to his house in Prenzlauer Berg.

A Military/Musical Dynasty

Moreover, Africans in Germany sometimes found themselves between the rock and the hard/place. Should they fight for this country?

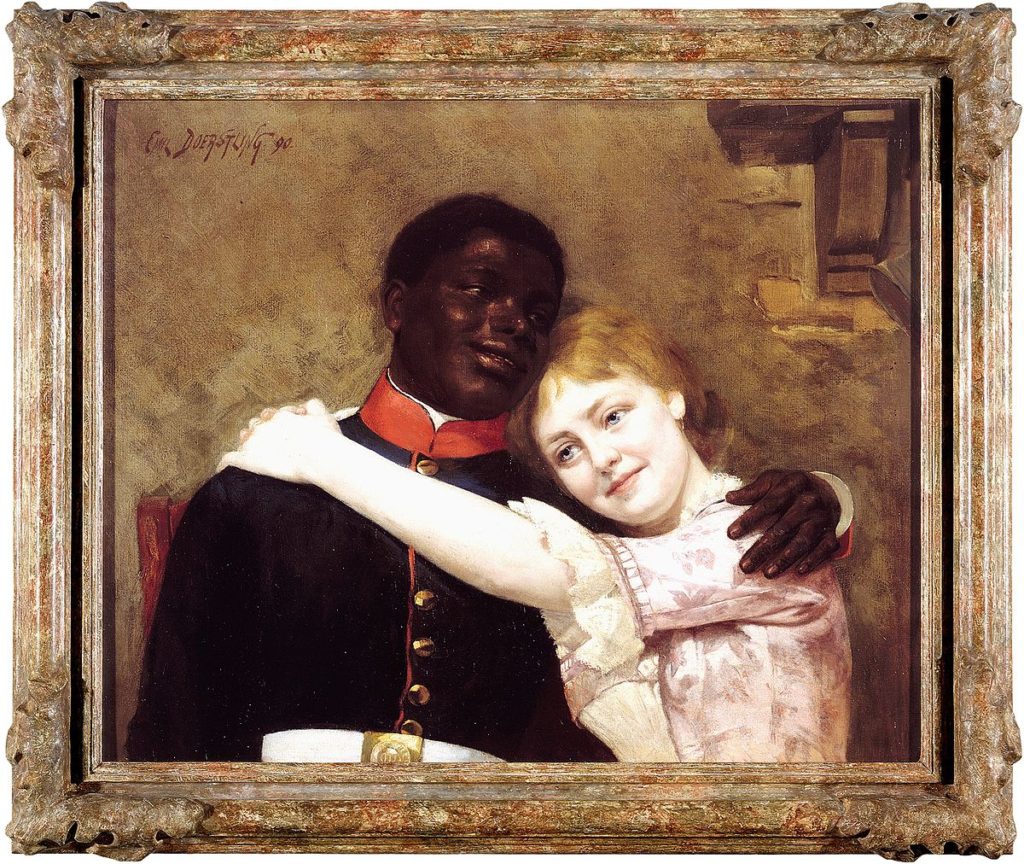

The Sabac el Cher family exemplifies this dilemma in three generations. Patriarch of the family, August Sabac el Cher , was born in Kordofan in today’s Sudan. He was brought to Egypt and given as a present to Prussian Prince Albert as a child who would serve him during his journey in the Middle East. From there, the party travelled to Berlin with the young August (whose family name is unknown – the name is based on a remote Germanization of the term for “good morning” in Arabic). He was taught German and became in later years a lackey in the prince’s court. He also participated in battles with the prince and received a golden watch from the Tsarina Alexandra for a campaign in the Caucasus. August participated in further wars as a Prussian officer, for which he received the Iron Cross and other medals. In 1867, he married Anna, the daughter of a Berlin businessman, with whom he had 3 children (one who died as a young child). August became later a senior servant in the court (with an official residence in the Prince Albert Palace, as well as private one in Kreuzberg) and remained in his job until a year before his untimely death of cancer.

August’s eldest, Gustav Sabac el Cher, was born in 1868 and became a celebrated military musician. After his retirement from the army, he worked as a Kapellmeister (head of an orchestra) living in Berlin with wife Gertrud and sons Horst and Herbert. In the late 1920s he opened a restaurant with a beer garden in Königs Wusterhausen, a picturesque town near Berlin, but had to leave the town (and close the business) with the Nazi takeover . He tried to open a café in the city centre, not far from the Jewish quarter, hoping to find more tolerance there, but the decorated officer encountered once again systematic racism. He died in 1934. One of his sons, Horst, died in the Second World War (both sons were conscripted and fighting for the racist regime that has ruined the family’s livelihood). Herbert survived the war, became the first violinist of the Mannheim orchestra. His son, Axel (born in 1937) is the last surviving Sabac el Cher.

Historical and Current Controversy

Not far from the place, where the Sabac El Cher family lived, you will find the Mohrenstraße (“Moor Street”), a street that also includes a train station named after it. The name is considered controversial today. Some claim, the name represents history of oppression, racism and colonialism. Others claim that the term “moor”, given to the street around 1707, does not represent colonialism per se (and/or that the name “moor” is not discriminatory or racist).

On July 3rd, 2020, Berlin’s public transportation authority, BVG, decided to change the controversial name. The city council of Mitte followed suit. The street (and probably also the station) will be named after Amo, who starred in the opening of this article. This would be an interesting development: near the place where Hitler’s Bunker once stood – a street after an African-German philosopher!

Cultural and Academic Appeal

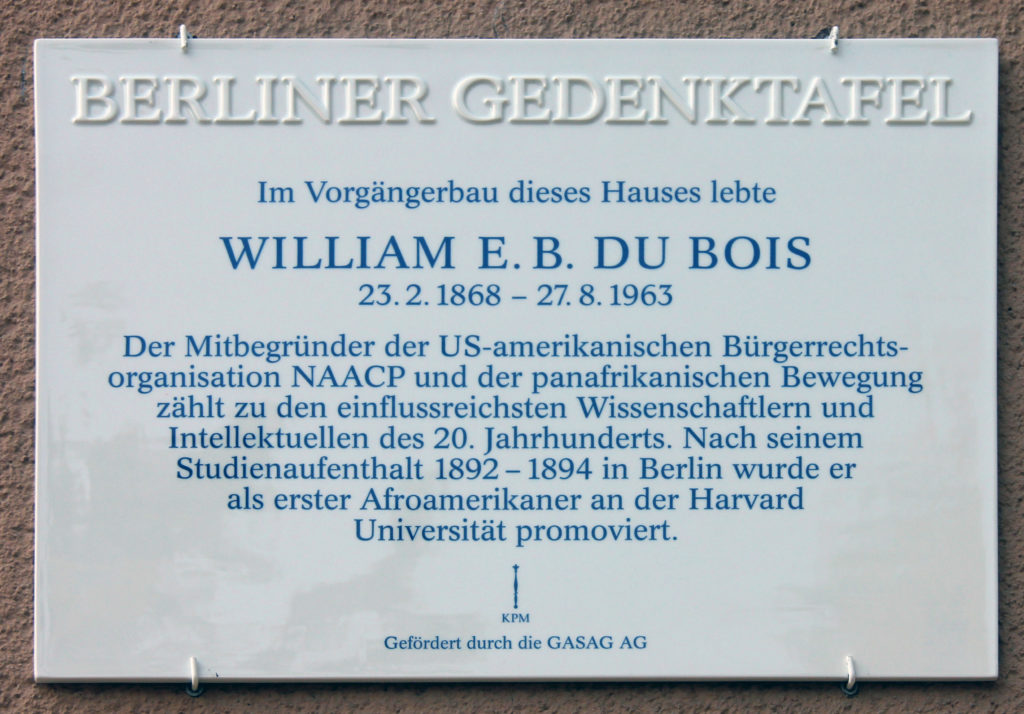

In the 20th Century, professionals, students and creatives have also found their way to Germany. One of the more prominent people of colour finding their way to Berlin was W.E.B Du Bois. Du Bois came in 1892 to study in Berlin’s Fridrich-Wilhelm University (today’s Humboldt University). The American Studies department of the university named its most prestigious lecture series after Du Bois, and is raising funds to place a memorial (you can donate here).

Du Bois was not the only African-American of his time in Berlin – others were Mary Church Terrel and Alain LeRoy Locke. Perhaps the most prominent African American associated with Berlin is Jesse Owens, who managed to amaze the world (and humiliate the “Race Theory”) in the 1936 Summer Olympics. A street near the Olympic stadium is named after him. Another brief visitor who left a lasting impression on the city is Martin Luther King, who visited East Berlin in 1964.

Part two of our article brings out the “Jewish Connection” . It started small, with a mystery of the presence of African Jews in Berlin, but became a whole range story!